It’s a common notion that people who have trouble sleeping at night must be harboring a guilty conscience. I often lose sleep, but guilt has never been the problem. What keeps me up at night are projects and other puzzles my brain keeps at, like a dog with a rawhide strip.

The project bouncing around in my head right now? Reproducing the casing, baseboard and plinth blocks from my brother-in-law’s Victorian. He bought this house from his parents, so this is the house he and my wife grew up in.

I decided I really wanted to do this project with hand tools. Anyone wondering why need only read Matt Bickford’s 2010 blog post on hollows and rounds. In fact, it only took the one sample chapter from Bickford’s book to convince me of his methods.

Owning just a few random hollows or rounds, and none of them with the right radius, how would I figure out which planes I would need, without dropping $1000 or more on a half set (or $3750 for a new half set from Bickford)? After a few comparisons based on the planes I had on hand, I had guesses, but not enough confidence to place an order for tools.

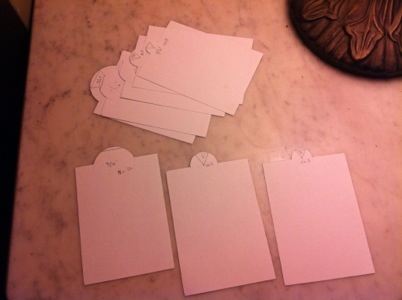

I started with what I knew: hollows and rounds are sized in increments of 16ths of an inch radii; typically they cut a 60 degree arc; the width of the iron (the chord) equals the radius. To get a positive ID, I came up with these gauges that I made from index cards.

Using these gauges, I was able to come up with the profiles I needed, with the confidence to place an order for tools. So why was I not able to sleep that night?

While I understood why my gauges worked, there were a few things that didn’t add up. I couldn’t figure out why my previous guesses (based on the irons from the hollows I had on hand) were so far off. The answer was in the geometry of the plane itself. While the profile of a hollow or round corresponds directly to the arc that it cuts, the same is not true of the plane iron.

Laying there, wide awake, it helped me to imagine a 1″ cylinder laying in my cove, with the No. 8 round forming the bottom of that cylinder. The cutting edge of the iron meets the bottom of the cylinder, bisecting the cylinder at an angle equal to the bed angle. The curve of the round’s plane iron, I finally realized, is an ellipse rather than the 60 degree arc of that 1″ circle. The same holds true for the hollow, except that my imagined cylinder rests within the work, and the hollow rests on top of it.

And now I can rest.

At least until I start to think about sharpening.